Abstract

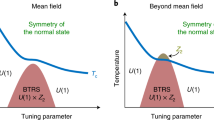

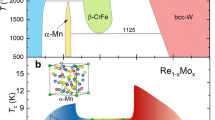

In general, magnetism and superconductivity are antagonistic to each other. However, there are several families of superconductors in which superconductivity coexists with magnetism, and a few examples are known where the superconductivity itself induces spontaneous magnetism. The best known of these compounds are Sr2RuO4 and some non-centrosymmetric superconductors. Here, we report the finding of a narrow dome of an \(s+is^{\prime}\) superconducting phase with apparent broken time-reversal symmetry (BTRS) inside the broad s-wave superconducting region of the centrosymmetric multiband superconductor Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 (0.7 ≲ x ≲ 0.85). We observe spontaneous magnetic fields inside this dome using the muon spin relaxation (μSR) technique. Furthermore, our detailed specific heat study reveals that the BTRS dome appears very close to a change in the topology of the Fermi surface. With this, we experimentally demonstrate the likely emergence of a novel quantum state due to topological changes of the electronic system.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

The code for calculating spontaneous fields within the Ginsburg–Landau model is available with the Supplementary Information files attached to this paper.

References

Lee, W.-C., Zhang, S.-C. & Wu, C. Pairing state with a time-reversal symmetry breaking in FeAs-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 217002 (2009).

Ng, T. K. & Nagaosa, N. Broken time-reversal symmetry in Josephson junction involving two-band superconductors. Europhys. Lett. 87, 17003 (2009).

Tanaka, Y. & Yanagisawa, T. Chiral ground state in three-band superconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 79, 114706 (2010).

Stanev, V. & Tesanovic, Z. Three-band superconductivity and the order parameter that breaks time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 81, 134522 (2010).

Carlstrom, J., Garaud, J. & Babaev, E. Length scales, collective modes, and type-1.5 regimes in three-band superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 84, 134518 (2011).

Hu, X. & Wang, Z. Stability and Josephson effect of time-reversal-symmetry-broken multicomponent superconductivity induced by frustrated intercomponent coupling. Phys. Rev. B 85, 064516 (2012).

Khodas, M. & Chubukov, A. V. Interpocket pairing and gap symmetry in Fe-based superconductors with only electron pockets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 247003 (2012).

Maiti, S. & Chubukov, A. V. s + is state with broken time-reversal symmetry in Fe-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 87, 144511 (2013).

Garaud, J. & Babaev, E. Domain walls and their experimental signatures in s + is superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 017003 (2014).

Platt, C., Thomale, R., Honerkamp, C., Zhang, S.-C. & Hanke, W. Mechanism for a pairing state with time-reversal symmetry breaking in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 85, 180502(R) (2015).

Maiti, S., Sigrist, M. & Chubukov, A. Spontaneous currents in a superconductor with s + is symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 91, 161102 (2015).

Garaud, J., Silaev, M. & Babaev, E. Thermoelectric signatures of time-reversal symmetry breaking states in multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097002 (2016).

Lin, S.-Z., Maiti, S. & Chubukov, A. Distinguishing between s + id and s + is pairing symmetries in multiband superconductors through spontaneous magnetization pattern induced by a defect. Phys. Rev. B 94, 064519 (2016).

Böker, J., Volkov, P. A., Efetov, K. B. & Eremin, I. s + is superconductivity with incipient bands: doping dependence and STM signatures. Phys. Rev. B 96, 014517 (2017).

Yerin, Y., Omelyanchouk, A., Drechsler, S.-L., Efremov, D. V. & van den Brink, J. Anomalous diamagnetic response in multiband superconductors with broken time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 96, 144513 (2017).

Vadimov, V. L. & Silaev, M. A. Polarization of spontaneous magnetic field and magnetic fluctuations in s + is anisotropic multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 98, 104504 (2018).

Chubukov, A. Itinerant electron scenario for Fe-based superconductors. Springer Series Mater. Sci. 211, 255–329 (2015).

Luke, G. M. et al. Time-reversal symmetry-breaking superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Nature 394, 558–561 (1998).

Biswas, P. K. et al. Evidence for superconductivity with broken time-reversal symmetry in locally noncentrosymmetric SrPtAs. Phys. Rev. B 87, 180503(R) (2013).

Hillier, A. D., Quintanilla, J., Mazidian, B., Annett, J. F. & Cywinski, R. Nonunitary triplet pairing in the centrosymmetric superconductor LaNiGa2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 097001 (2012).

Mazin, I. I. Superconductivity gets an iron boost. Nature 464, 183–186 (2010).

Kuroki, K. et al. Unconventional pairing originating from the disconnected Fermi surfaces of superconducting LaFeAsO1 − xFx. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 087004 (2008).

Ahn, F. et al. Superconductivity from repulsion in LiFeAs: novel s-wave symmetry and potential time-reversal symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. B 89, 144513 (2014).

Ding, H. et al. Observation of Fermi-surface-dependent nodeless superconducting gaps in Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2. Europhys. Lett. 83, 47001 (2008).

Kordyuk, A. A. ARPES experiment in fermiology of quasi-2D metals. Low Temp. Phys. 40, 286–296 (2014).

Xu, N. et al. Possible nodal superconducting gap and Lifshitz transition in heavily hole-doped Ba0.1K0.9Fe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 220508(R) (2013).

Malaeb, W. et al. Abrupt change in the energy gap of superconducting Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 single crystals with hole doping. Phys. Rev. B 86, 165117 (2012).

Grinenko, V. et al. Superconductivity with broken time-reversal symmetry in ion-irradiated Ba0.27K0.73Fe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 95, 214511 (2017).

Bobkov, A. M. & Bobkova, I. V. Time-reversal symmetry breaking state near the surface of s ±-superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 84, 134527 (2011).

Liu, Y. & Lograsso, T. A. Crossover in the magnetic response of single-crystalline Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 and Lifshitz critical point evidenced by Hall effect measurements. Phys. Rev. B 90, 224508 (2014).

Hirano, M. et al. Potential antiferromagnetic fluctuations in hole-doped iron-pnictide superconductor Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 studied by 75As nuclear magnetic resonance measurement. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 81, 054704 (2012).

Eilers, F. et al. Strain-driven approach to quantum criticality in AFe2As2 with A = K, Rb and Cs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 237003 (2016).

Drechsler, S.-L., Johnston, S., Grinenko, V., Tomczak, J. M. & Rosner, H. Constraints on the total coupling strength to bosons in the iron based superconductors. Phys. Status Solidi B 254, 1700006 (2017).

Drechsler, S.-L. et al. Mass enhancements and band shifts in strongly hole-overdoped Fe-based pnictide superconductors: KFe2As2 and CsFe2As2. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 31, 777–783 (2018).

Bud’ko, S. L., Ni, N. & Canfield, P. C. Jump in specific heat at the superconducting transition temperature in Ba(Fe1 − xCox)2As2 and Ba(Fe1 − xNix)2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 79, 220516(R) (2009).

Bang, Y. & Stewart, G. R. Superconducting properties of the s ±-wave state: Fe-based superconductors. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 123003 (2017).

Ota, Y. et al. Evidence for excluding the possibility of d-wave superconducting-gap symmetry in Ba-doped KFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 89, 081103(R) (2014).

Watanabe, D. et al. Doping evolution of the quasiparticle excitations in heavily hole-doped Ba1 − xKxFe2As2: a possible superconducting gap with sign-reversal between hole pockets. Phys. Rev. B 89, 115112 (2014).

Cho, K., Konczykowski, M., Teknowijoyo, S., Tanatar, M. A. & Prozorov, R. Using electron irradiation to probe iron-based superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 31, 064002 (2018).

Yoshida, T. et al. Orbital character and electron correlation effects on two- and three-dimensional Fermi surfaces in KFe2As2 revealed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Front. Phys. 2, 17 (2014).

Blanter, Y. M., Kaganov, M. I., Pantsulaya, A. V. & Varlamova, A. A. The theory of electronic topological transitions. Phys. Rep. 245, 159–257 (1994).

Hodovanets, H. et al. Fermi surface reconstruction in Ba1−xKxFe2As2 (0.44 ≤ x ≤ 1) probed by thermoelectric power measurements. Phys. Rev. B 89, 224517 (2014).

Grinenko, V. et al. Superconducting specific-heat jump \({C}_{{\rm{el}}}\propto {T}_{{\rm{c}}}^{\beta }\)(β≈ 2) for K1−xNaxFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 89, 060504(R) (2014).

Hardy, F. et al. Strong correlations, strong coupling and s-wave superconductivity in hole-doped BaFe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 94, 205113 (2016).

Hatlo, M. et al. Developments of mathematical software libraries for the LHC experiments. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 52, 2818–2822 (2005).

Grinenko, V. et al. Superconducting properties of K1−xNaxFe2As2 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 90, 094511 (2014).

Kihou, K. et al. Single-crystal growth of Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 by KAs self-flux method. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 85, 034718 (2016).

Amato, A. et al. The new versatile general purpose surface-muon instrument (GPS) based on silicon photomultipliers for μSR measurements on a continuous-wave beam. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 093301 (2017).

Suter, A. & Wojek, B. M. Musrfit: A free platform-independent framework for μSR data analysis. Phys. Procedia 30, 69–73 (2012).

Koepernik, K. & Eschrig, H. Full-potential nonorthogonal local-orbital minimum-basis bandstructure scheme. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1743–1757 (1990).

Garaud, J., Silaev, M. & Babaev, E. Microscopically derived multi-component Ginzburg–Landau theories for s + is superconducting state. Proc. Ninth International Conference on Vortex Matter in Nanostructured Superconductors 533, 63–73 (2017).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by DFG (GR 4667/1, GRK 1621 and SFB 1143 project C02). The work of M. A. Silaev was supported by the Academy of Finland (project no. 297439). The work of I.E. was carried out with support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the framework of Increase Competitiveness Program of NUST MISiS grant no. К2-2020-001. This work was partly performed at the Swiss Muon Source (SμS), PSI, Villigen. We acknowledge fruitful discussions with A. Amato, S. Borisenko, E. Babaev, A. Charnukha, O. Dolgov, C. Hicks, C. Meingast and A. de Visser. We especially acknowledge D. Efremov for support with DFT calculations. We are grateful for technical assistance from C. Baines.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.G. designed the study, initiated and supervised the project and wrote the paper, performed the μSR, specific heat, magnetic susceptibility and X-ray diffraction measurements. R.S. performed the μSR experiments. K.K. and C.H.L. prepared Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 single crystals in the doping range 0.65 ≲ x ≲ 0.85. I.M. and S.A. prepared Ba1 − xKxFe2As2 single crystals with x ≈ 0.98. P.C. performed and W.S. supervised TEM measurements. K. Nenkov performed specific heat and magnetization measurements. B.B, R.H. and K. Nielsch supervised the research at IFW. S.-L.D. provided interpretation of the experimental data. V.L.V. and M.A.S. performed calculation of the spontaneous magnetic fields in the BTRS state. P.A.V. and I.E. analysed specific heat in the BTRS state. H.L. performed μSR experiments and supervised the research at PSI. H.-H.K. initiated the project and supervised the research. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Physics thanks Thomas A. Maier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Normal state depolarization rate.

(Left axis) Doping dependence of the normal state depolarization rate Λ0 extrapolated to zero temperature as shown in Fig. 3 of the main text obtained assuming temperature independent σ. The error-bars in the absolute value of the depolarization rate is caused by uncertainty in the background contribution. (Right axis) Doping dependence of the static susceptibility measured at T = 20 K given in Fig. 2a of the main text. Dashed lines are guides to the eyes. Inset: Doping dependence of the temperature independent depolarization rate σ.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The structure of the spontaneous fields and currents in an s + is superconductor.

The structure of the spontaneous magnetic field (left panels) and spontaneous currents (right panels) produced by the spherically-symmetric inhomogeneity in anisotropic s + is and s − is states. In the left panels the red/blue arrows show clockwise/counter-clockwise parts of the magnetic field distribution. The clockwise and counter-clockwise field is generated by the supercurrents with jz > 0 (red arrows) and jz < 0 (blue arrows) shown in the right panels. Notice that the magnetic field and current directions are opposite in s + is and s − is states. The length-scale in the axes is given in units of the zero-temperature coherence length ħvF/Tc. The x, y and z axes are chosen along the a, b and c crystallographic directions, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Anisotropy of the internal fields in an s + is superconductor.

Two orthogonal components of the normalized internal spontaneous fields Bint/Bc2 depending on a strength of the variation of the SC coupling constant Δη2 due to an inhomogeneity. Inset: Δη2 dependence of the anisotropy ratio of the internal fields γint. In the main text Δλ ≡ aΔη2 with a ~ 1 (see section 6 in the Supplementary information for details).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Electrical resistivity.

(a) Temperature dependence of the resistivity of the Ba1−xKxFe2As2 single crystals with different doping levels. Inset: Zoom into the temperature range close Tc. (b) The resistivity versus squared temperature. Dashed curves are the fits using ρ(T) = ρ0 + AFLT2. Inset: Doping dependence of the AFL coefficient. The data for x = 1 are taken from Ref. 46.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Impurity effect on the phase diagram.

Doping dependence of the residual resistivity ρ0 of the Ba1−xKxFe2As2 single crystals (green triangles, right axis) on top of the phase diagram with the region close to the BTRS dome.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–12 and discussion.

Supplementary Software 1

The code for calculating spontaneous fields within the Ginsburg–Landau model. Software_1 file contains the code implementing relaxation minimization of the free energy functional defined on the triangular grid which is constructed in Software_2 file. The parameters of the Ginzburg–Landau model like temperature, pairing constants and effective masses are passed to the constructor of the main class SPlusIS_XZ. Parameter ‘kappa’ defines the ratio between the London penetration depth and the coherence length (the default value None corresponds to the infinite penetration depth), parameter ‘spis’ distinguishes between the s + is and s + id cases. The method ‘solve’ of this class minimizes the free energy functional.

Supplementary Software 2

The code for calculating spontaneous fields within the Ginsburg–Landau model. Software_2 file contains a class that describes a triangular grid and vector operations like gradient, divergence and curl.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Susceptibility data and raw SQUID data from Fig. 2a Electronic specific heat from Fig. 2b Tc, Electronic specific heat/T, Sommerfeld coefficient versus K-doping from Fig. 2c and 2d.

Source Data Fig. 3

Zero-field muSR time spectra from Fig. 3a, 3b, and 3c muon spin depolarization rate at different temperatures and magnetic susceptibility at B∥ab = 0.5 mT from Figs. 3d, Fig. 3e, Fig. 3f, Fig. 3g and Fig. 3h.

Source Data Fig. 4

Muon spin depolarization rate at different temperatures for Pμ∥c, and for Pμ∥a from Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b.

Source Data Fig. 5

Tc defined from specific heat and magnetization data, TBTRS temperature, electronic specific heat, experimental Sommerfeld coefficient, calculated DOS, calculated Sommerfeld coefficient \({\gamma }_{{\rm{DFT}}}/{\gamma }_{{\rm{DFT}},\min }\) and calculated mean field \({T}_{{\rm{c}}}/{T}_{{\rm{c}},\min }\) versus K-doping.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grinenko, V., Sarkar, R., Kihou, K. et al. Superconductivity with broken time-reversal symmetry inside a superconducting s-wave state. Nat. Phys. 16, 789–794 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-0886-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-0886-9

This article is cited by

-

Signatures of a surface spin–orbital chiral metal

Nature (2024)

-

High-order time-reversal symmetry breaking normal state

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2024)

-

Nodal s± pairing symmetry in an iron-based superconductor with only hole pockets

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Calorimetric evidence for two phase transitions in Ba1−xKxFe2As2 with fermion pairing and quadrupling states

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Spectroscopic signatures of time-reversal symmetry breaking superconductivity

Communications Physics (2022)